In Search of God

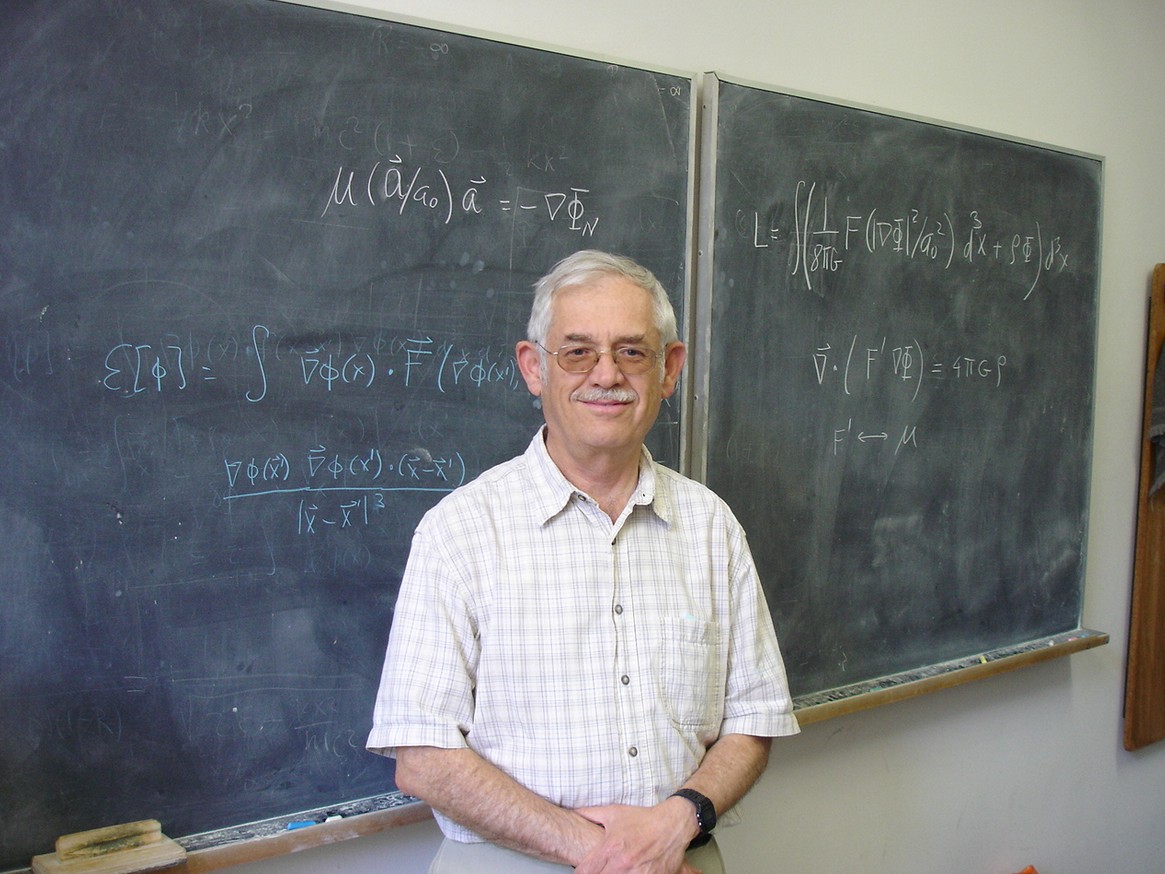

Professor Jacob Bekenstein: The Israeli Physicist Who Proved Stephen Hawking Wrong and United Science with Faith

The humble genius behind black hole theory, Israel Prize laureate, and a devout scientist who saw the universe as the work of God

- Hidabroot

- |Updated

Professor Jacob Bekenstein was one of the great theoretical physicists of our era. Much of his fame in scientific circles stemmed from his famous debate with Stephen Hawking about the true nature of black holes — celestial objects so dense that not even light can escape them. The outcome of that debate was clear: Bekenstein was right.

In his bestselling book A Brief History of Time, Hawking later admitted: “It turns out that Bekenstein was, in fact, correct.”

The Man Who Changed Our Understanding of the Universe

Bekenstein’s work transformed physics. His insights into black hole thermodynamics revealed a profound connection between gravity, entropy, and information — concepts that continue to shape modern cosmology and quantum theory.

Despite his groundbreaking contributions and collaborations with world-renowned scientists, Bekenstein avoided the spotlight. As The Washington Post wrote after his death: “Dr. Bekenstein was highly respected among his peers, but his achievements never brought him public fame.”

A Humble Teacher with a Love for Discovery

Dr. Ofer Metuki, a physics doctoral student at the Hebrew University who studied under Bekenstein, described him beautifully in his blog: “He was one of the most humble people I’ve ever met. What drove him was the desire to explore, to understand the world, and to pass that knowledge on.”

Metuki recalled how, in 2005, Bekenstein won the Israel Prize — the nation’s highest honor, right in the middle of the semester. “The day after his award, he walked into class as usual. We all stood and clapped. He stood there, embarrassed, waiting for the applause to fade, and then simply turned to the board and started teaching.”

That quiet dignity was his trademark.

Awards Never Defined Him

In addition to the Israel Prize, Bekenstein received the Rothschild Prize and the Wolf Prize — one of the most prestigious awards in the scientific world, often a prelude to a Nobel Prize.

However these honors didn’t change him. While others might have reveled in the spotlight, he remained focused on truth and discovery.

Science and Faith in Harmony

Unlike Stephen Hawking, who declared himself an atheist later in life, Bekenstein was an observant Jew, wearing a kippah and speaking openly about his faith.

He once said: “I see the world as the product of the work of the Holy One, blessed be He. He established very precise laws, and we take great pleasure in discovering them — seeing how everything fits together.”

In 2006, when Hawking claimed that the Big Bang did not require divine involvement, The Jerusalem Post turned to Bekenstein for a response.

His reply was calm yet firm: “Hawking’s new declarations are a bit too simplistic. We learn about the universe through observation and experimentation, but our abilities are limited, and we can misinterpret the laws of physics. Even many scientists who don’t believe in God find his conclusions exaggerated.”

He added: “More people will agree with Hawking’s call to colonize the Moon or other planets than with his claim that the universe didn’t need divine involvement. Even if we could reproduce the conditions of the Big Bang in a lab, it wouldn’t mean we could create a universe.”

Professor Jacob Bekenstein

Professor Jacob BekensteinGratitude Before Greatness

Perhaps the story that captures him best is what happened after he won the Wolf Prize three years before his death. Friends and colleagues tried to call to congratulate him — but no one could reach him.

He wasn’t home because he had gone to the Western Wall in Jerusalem, to thank God for the honor.

A Legacy of Wonder and Humility

Professor Jacob Bekenstein embodied a rare balance — a mind of genius and a heart of faith. His life proved that science and spirituality can coexist, not as rivals but as partners in humanity’s search for truth.

He didn’t seek fame, yet his discoveries reshaped our understanding of the cosmos. He didn’t preach religion, yet his faith infused his science with reverence.

May his memory be blessed.