Parashat Emor

Why the Torah Bars Priests with Physical Defects — but Honors the Spirit of Every Soul

Jewish thought teaches that physical imperfection never limits spiritual greatness — it only safeguards the dignity of sacred representation

In Parshat Emor, the Torah states: “Speak to Aaron, saying: Any man among your descendants throughout their generations who has a blemish shall not approach to offer the food of his God.”

(Vayikra 21:17)

Today, society goes to great lengths to ensure equality and accessibility for people with disabilities. Excluding someone from a role because of a physical impairment is considered discrimination.

In many ancient cultures, however, disability was viewed as a curse or a mark of divine rejection. In Babylon, for example, a person with a disability could not become a prophet. Even the Qumran sect (the Dead Sea community during the Second Temple period) barred anyone with a physical defect from joining, seeing such individuals as impure and unworthy of spiritual elevation.

The Torah’s perspective however is fundamentally different, and there is no trace of such an attitude in Judaism

The Torah’s View: A Physical Defect Does Not Diminish the Soul

Many of Israel’s greatest figures had physical limitations:

Yitzchak lost his sight in old age — and in that state, he received prophecy and divine inspiration.

Achiya HaShiloni, whose “eyes were dim from age,” could not see, yet his spiritual vision “ranged over the entire earth.”

Yaakov limped after wrestling with the angel — yet God revealed Himself to him.

Moshe, the greatest of all prophets, had a speech impediment: “I am slow of speech and slow of tongue.”

Some commentators even suggest that Chulda the Prophetess may have been blind. When King Yoshiyahu (Josiah) sent messengers to her to inquire about the Torah scroll that had been found, they did not bring the scroll itself — perhaps because she could not see it. She was known to sit in a fixed location “in the Second Quarter” of Jerusalem, near the Chulda Gates on the southern side of the Temple Mount, where tradition says she was later buried.

These examples illustrate that in Judaism, physical imperfection never implies spiritual inferiority.

Why a Priest with a Defect Cannot Serve in the Temple

The restriction applied only to priests performing public service in the Temple, not to their personal worth or holiness. The priest’s role was representative, standing before the nation as an emissary of God. The requirement for physical wholeness symbolized dignity and harmony, not superiority.

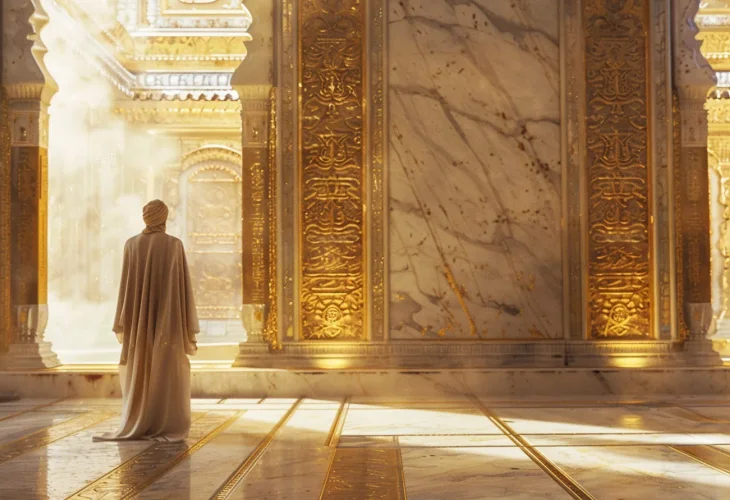

Just as the Temple itself was built with beauty and grandeur — not because holiness depends on aesthetics, but because external splendor reflects inner reverence, so too, its servants were to embody that same sense of completeness.

Maimonides: Representation and Human Perception

Maimonides (in Guide for the Perplexed, III:45) explains that this law reflects the psychological effect of appearance on the public: “For the common people do not honor a person for his true inner perfection, but for the completeness of his limbs and the beauty of his garments. The goal was that this House and its servants be held in reverence by all.”

If a visibly disabled priest were to serve in the Temple, some may wrongly treat the service or the sanctuary with less respect. The same principle applies to the Temple building itself: if it were shabby or poorly built, people’s sense of awe would diminish.

Sefer HaChinuch: The Distraction of Imperfection

Sefer HaChinuch (Mitzvah 275) adds another layer: “It is possible that the completeness of form hints at ideas through which man’s thoughts are purified and uplifted. Therefore, it is not fitting that there be any deviation from that form, lest the observer’s attention be distracted and his mind drawn away from the sacred purpose.”

According to this explanation, a visible defect can distract observers, shifting their focus from spiritual concentration to curiosity or pity — just as the sages taught that a priest with stained or colored hands should not bless the congregation, because people would stare at his hands instead of focusing on prayer.

The Principle

The Torah’s principle is clear:

In matters of personal holiness, wisdom, or spirituality, there is no difference between a person with a disability and anyone else.

In representative functions — those performed publicly on behalf of the people, physical completeness serves to maintain reverence and focus.

The Torah never suggests that a blemish reflects sin or inferiority. On the contrary, the Torah affirms that a person’s inner soul and spiritual stature remain entirely untouched by any external limitation.