Issues in the Bible

The Eternal Wisdom of Ki Teitzei: When the Torah Speaks to a Changing World

Discover how the laws of the captive woman, the ancient monument, and Amalek reveal the Torah’s living spirit — unchanging in truth, yet ever relevant to the challenges of each generation

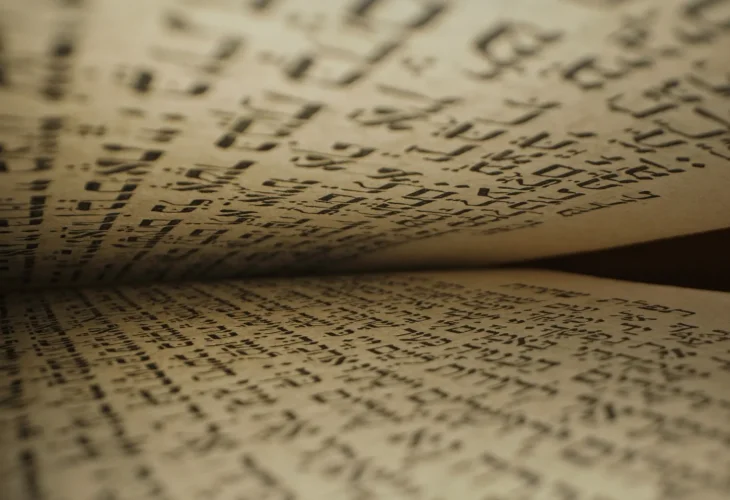

(Photo: shutterstock)

(Photo: shutterstock)In Parshat Ki Teitzei, we find many commandments — yet among them, three stand out as remarkably unusual. The portion opens with the law of the beautiful captive woman (eshet yefat to’ar), in the middle appears the prohibition of the matzevah (a private altar or monument), and it concludes with the commandment to eradicate Amalek.

What is unique about these three mitzvot?

The Beautiful Captive: A Command Against One’s Desire

Although the Torah explicitly legislates the case of a yefat to’ar, our sages emphasize that this is not the ideal will of God, but a concession “against the evil inclination.” In other words, the Torah sometimes recognizes human weakness, and provides a path to channel it rather than suppress it. The commandment is not to encourage the act, but to prevent something worse.

The Monument: Once Sacred, Now Forbidden

The Torah strictly forbids the building of a matzevah — a sacred pillar or altar, even though in earlier generations it was a holy practice. Avraham built such monuments to God, and even Moshe erected one. However, the sages explain that once idolaters adopted the same practice, the Torah declared it “hated by the Lord your God.” The same act that once expressed holiness became corrupted by its misuse.

This teaches that the Torah is not fossilized. Its holiness lies not in stone, but in its living relationship with the moral and spiritual state of the world. A person cannot say, “I will do what Avraham did” without understanding the spiritual context. What was once righteous can later become misguided — and the Torah itself reveals when such shifts occur.

Eradicating Amalek: Remembering the Eternal Battle Against Evil

The commandment to destroy Amalek presents a paradox: on one hand, we cannot fulfill it literally, for the nations were long ago mixed by Sancheriv; yet on the other, we are commanded to remember it forever. Each year we read “Remember what Amalek did to you” — a mitzvah that cannot be performed physically but remains spiritually binding.

This commandment reveals that Torah law is not bound by circumstance. The physical nation of Amalek may be gone, but the idea of absolute evil — the force that seeks to destroy faith and morality, remains, and must be confronted in every generation.

Eternal Law in a Changing World

At first glance, these three mitzvot — the captive woman, the monument, and Amalek, seem to contradict the idea of an eternal Torah. If the Torah is eternal, why do its applications appear to change?

The answer lies in the true nature of eternity. Eternality does not mean unchanging stagnation. Stones and seas last forever, but they do not live. True eternity is dynamic — it overcomes change, it endures through adaptation, and it continues to illuminate every new circumstance without losing its essence.

The Torah’s eternity is the eternity of life, not of stone. Its laws breathe, respond, and reveal divine wisdom through history. Without the Oral Torah, one might misread the Written Torah as frozen and literal — as did the ancient sects who refused the oral tradition: the Samaritans, Sadducees, and Karaites. They read “Let no man go out from his place on the Shabbat” literally and therefore refused to leave their homes; they read “Do not kindle a fire” and sat in darkness eating cold food.

The Oral Torah restores movement, intention, and life to the written word. It teaches that “When you go out to war” means if you go — not that you should go. It teaches that the matzevah is now forbidden, not because God changed, but because humanity did.

The Living Law vs. the Law of Stone

The Torah’s adaptability is not weakness but proof of its divine vitality. It moves with life, while maintaining its moral axis. By contrast, the laws of Hammurabi — carved in stone in the days of Avraham, remain etched on tablets, lifeless relics of a vanished world. No one today finds them relevant to their lives. The Torah however, given thousands of years ago, continues to shape human conscience, family, justice, and faith.

Three Eternal Battles

Through these three commandments, the Torah outlines the three great moral wars that define the human condition:

The war against the evil inclination – represented by the captive woman.

The war against idolatry and corruption of truth – represented by the prohibition of the monument.

The war against absolute evil – represented by Amalek.

These are not ancient battles, but the inner and outer wars of every generation. Precisely because of their depth and complexity, they remain eternal.

The Message of Ki Teitzei

When the Torah says “When you go out to war”, it is not only speaking of the battlefield. It speaks of the human struggle — against desire, against false worship, and against the forces that mock holiness.

Because the Torah continues to guide us in these wars — spiritually, morally, and practically, it remains the only code of law whose words, though ancient, are still alive.

Laws carved in stone die with their empires. But a law engraved in the human heart, lives forever.