Unlocking Manuscript Mysteries: Ancient Texts and Hidden Stories

Dr. Jacob Fox, a manuscript expert at the National Library, delves into discovering and decoding ancient texts, revealing fascinating secrets of the past.

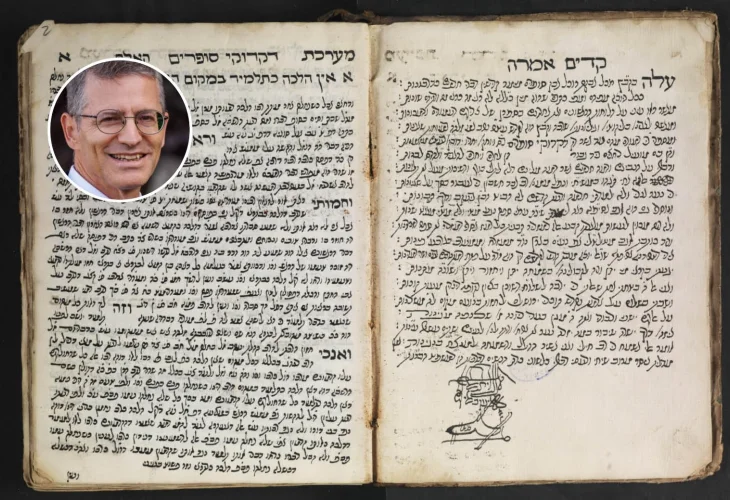

An example of Eastern writing from the early 19th century, with a stylistic signature. National Library of Jerusalem, Manuscript Ms. Heb. 3634. Inset: Dr. Jacob Fox

An example of Eastern writing from the early 19th century, with a stylistic signature. National Library of Jerusalem, Manuscript Ms. Heb. 3634. Inset: Dr. Jacob FoxDr. Jacob Fox is a manuscript expert at the National Library, but ask him, and he describes himself as an adventurer embarking daily on a riveting journey through a time tunnel that whisks him hundreds of years back to fascinating events, famous figures, and a wealth of information often unknown to the public.

"I've been working in the manuscript department since 2011," he shares, "and the discoveries here are continually fascinating. The world of manuscripts is rich, and unlike other libraries, the National Library manages a catalog not only of the items in its possession but of all Hebrew manuscripts globally. We have tens of thousands of ancient manuscripts, all of which undergo a diagnostic process where we attempt to delve into their depths and learn as much as we can."

According to him, manuscripts arrive through archives from various libraries and photographs sent from around the world. Some manuscripts also come physically, brought by collectors or even private individuals who hand them over for photographing and documentation. They ask experts to examine the manuscripts and tell them what secrets they hold.

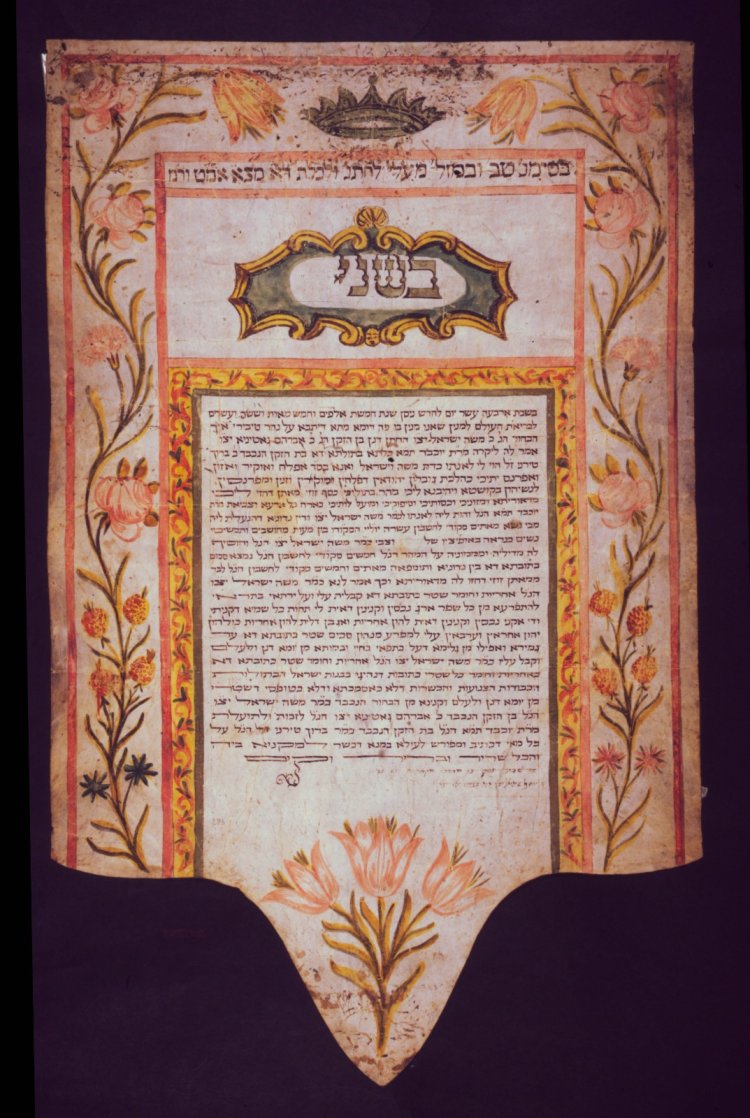

Ketubah from Rome 1766

Ketubah from Rome 1766Read, Decode, Understand

The task of decoding manuscripts, as it turns out, is quite complex. "Let's start with the most basic challenge," says Dr. Fox, "we're all familiar with trying to decipher someone's handwriting and failing because it's unclear or illegible. Handwriting isn't print; it can be challenging, especially when the style is unfamiliar. There are significant differences in how letters were written between countries in the past. The writing style in Italy was different from that in Morocco, and Turkish writing wasn't like that in Iraq. Writing from eight hundred years ago differs from that two hundred years ago."

So how can we really decode these manuscripts?

"Of course, there are various ways, but it's really not easy, and there are no shortcuts. You must sit down, work, check, and invest, and naturally, the more you do so, the more experience you gain. Often, the challenge arises at the end of a manuscript, with the signature of its author. Decoding signatures is much more complex than deciphering manuscripts, especially when dealing with Ashkenazi signatures, where letters sometimes connect, or with elaborate signatures typical of Moroccan and Eastern Jews. Identifying the manuscript's owner requires familiarity with all signature types, yet occasionally, I admit that I still cannot determine who signed it."

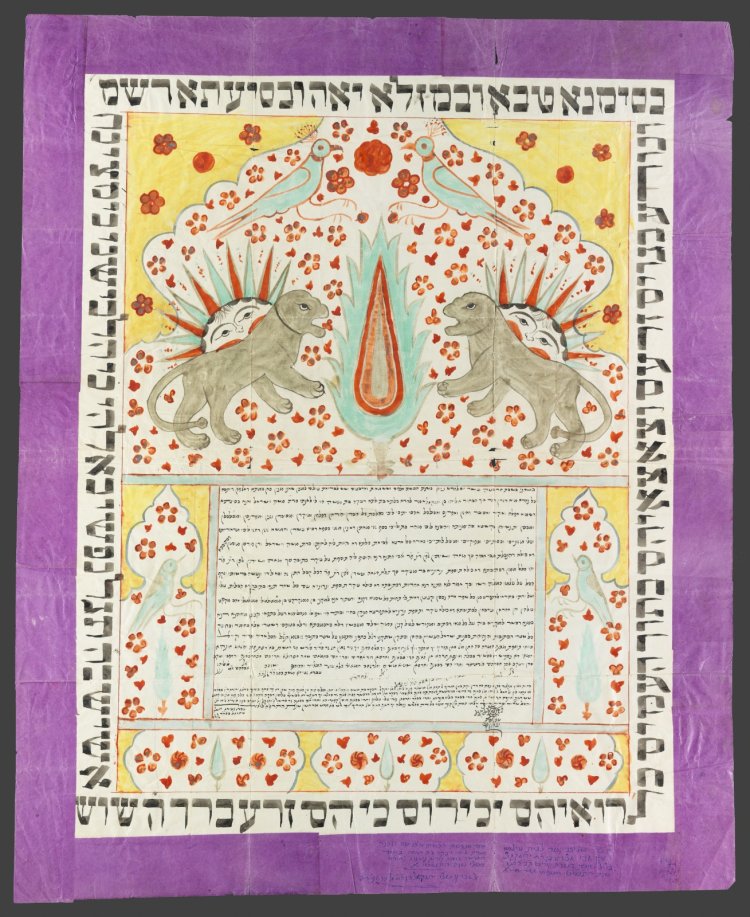

Ketubah from Isfahan, Iran 1886

Ketubah from Isfahan, Iran 1886The Victory of Watermarks

Another task Dr. Fox faces when decoding manuscripts is determining the year of origin for the document in hand. "The main tool we use is watermarks," he explains. "These marks have characterized paper since its creation in the 13th century in Europe. During the production process, a kind of paste was placed on a plate, creating shapes and letters that weren't visible in the paper itself. However, when viewed against light, these shapes became apparent due to the impressions left by the plate.

"As far as we know, these marks were replaced every twenty years at most. Researchers have collected examples of watermarks over the years and created detailed catalogs with thousands of examples. Thus, if a manuscript has watermarks identical to those in a catalog, we can definitively say it belongs to a ten-year period relative to the catalog's date."

Dr. Fox shares a fascinating recent story about this process: "About two weeks ago, someone contacted us about a book with a censorship signature from 1610. I asked him to send us the watermarks found in it, and upon examining them, I could identify definitively that the mark was from 1780. I asked him to bring the book to the library, and after a thorough examination, it turned out to be astonishing - it was indeed a book from an early print, but it lacked pages. Somebody had later restored those missing pages and even copied the original censorship signature. This proved what is known in the manuscript world - if you have an exact watermark, it unequivocally indicates the manuscript's age.

"A similar story occurred in recent years when someone claimed to have a siddur from the first Hebrew print predating Gutenberg's Bible in 1453. He substantiated this with the paper's watermarks and had endorsements from significant figures knowledgeable in the field. However, upon in-depth examination, it turned out those who dated the book were wrong. They didn't find a precise mark from that period but rather the watermark's style, which isn't accurate at all, suggesting the siddur was printed later than thought."

Dr. Fox emphasizes: "A manuscript is anything written by hand, meaning even a ketubah signed by two witnesses is considered a manuscript. Once we decode names from ketubot that can be over 900 years old, they provide valuable genealogical information and teach us about people and families not found in books or anywhere else. We also encounter handwritten contracts, documents, or even diaries people wrote for themselves without intending to publish them, offering insights into Jewish settlements and customs at different times and places.

"We also have a large collection of manuscripts in Persian," Dr. Fox adds, "revealing many unknown aspects. It turns out that the Persian Jewish community had a highly developed literary culture, with many poems, songs, adaptations, biblical books, and other rhymed works written in Hebrew letters but in Persian. It's massive and fascinating content, a true treasure trove."

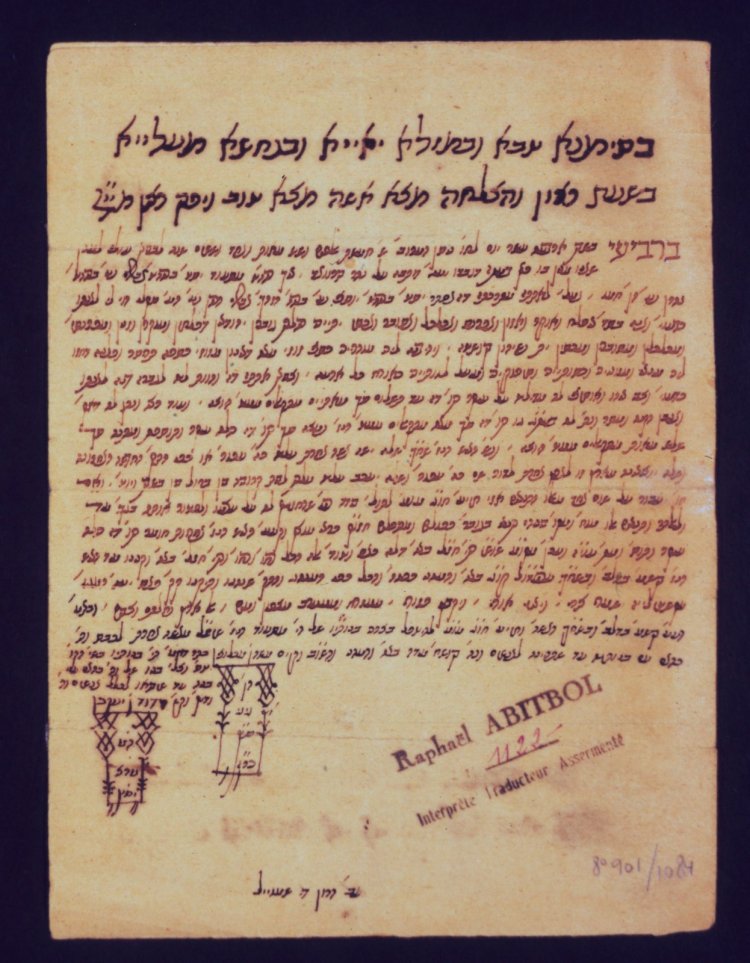

Ancient Ketubah from Debdou, Morocco 1901

Ancient Ketubah from Debdou, Morocco 1901The Story Behind the Script

Behind many manuscripts are stories shedding light on historical narratives. "We also have a huge collection of Passover Haggadot, many very ancient ones owned by wealthy Jewish families before World War II, stolen by the Nazis," Dr. Fox shares. "Take, for instance, the manuscript called 'Rothschild Haggadah,' which has a fascinating history. Until 1939, the Haggadah belonged to the Rothschild family, but during World War II, it was stolen by the Nazis and disappeared. After the war, Dr. Fred Murphy, a Yale University graduate, acquired it, bequeathing it to the university library. Only in 1980 was the Haggadah recognized as Rothschild family property and returned to its owners, who donated it to the National Library.

"Incidentally, this Haggadah was missing three pages, seemingly torn out even before the Rothschild family's acquisition. Recently, two of the missing pages were offered for sale and acquired for the library, thanks to the generosity of two anonymous donors."

Dr. Fox also shares a captivating genealogical tale: "Rabbi David de Silva, a well-known 18th-century Jerusalem scholar, was the son of Rabbi Hezekiah de Silva, who wrote the book 'Pri Hadash.' We also know Rabbi Yonah Navon, considered the teacher of the Chida, one of Israel's greatest scholars. Until now, it was known and documented that Rabbi Navon was married to the Chida's aunt. Yet one day, a 'Pri Hadash' book arrived with a dedication in Rabbi David de Silva's handwriting, stating: 'I give this book as mishloach manot to my son-in-law, Yonah Navon.'

"This revealed that Rabbi Yonah Navon, whom we knew was married to the Chida's aunt, had been previously or subsequently married to Rabbi David de Silva's daughter. This was information unknown from any other source, and if not for the handwritten note in the book that reached us, it would have remained unknown. Naturally, this is just a small example of the historical information embedded in manuscripts, and we encounter such things endlessly. As I mentioned earlier, the world of manuscripts is vast and full of discoveries. However, of course, there are also manuscripts that, unfortunately, we cannot definitively identify or date. While it is evident they carry crucial information, it remains hidden, and perhaps we will never decode it."

What about artificial intelligence? Are you using it in your work?

"Artificial intelligence is undoubtedly our next hope. Already, there are developments allowing AI to read printed letters from manuscripts, even in various styles, greatly advancing the field of manuscript decoding. The next stage is expected to involve reading writings that aren’t in printed letters, and several places worldwide are working on such developments and producing results. This will be a breakthrough because when we input the data into the computer, it will tell us the style, time, and location it was written, doing so better than any researcher, as it recognizes nuances that the human eye cannot perceive. It is one of the fields receiving significant investment today, and though it takes a long time, we are eagerly anticipating this significant breakthrough."