Dreaming of Home: A Rabbi's Hope for Gush Katif

Rabbi Yosef Elnekaveh dreams of returning to Gush Katif, a hope he believes is nearing reality.

Demolition of the Ganei Tal settlement in Gush Katif, August 2025 (Photo: Yossi Zamir, Flash 90)

Demolition of the Ganei Tal settlement in Gush Katif, August 2025 (Photo: Yossi Zamir, Flash 90)Rabbi Yosef Elnekaveh's memories of his days in Gush Katif remain unmatched by any other experiences. Even now, 19 years after he was uprooted from his home during the Disengagement Plan, they remain vivid in his memory, and he refuses to let them go.

A map of Gush Katif lays close to Rabbi Elnekaveh's heart, as he served as the regional rabbi. Every street, path, yeshiva, house, greenhouse, and crop is etched in his memory for a single reason. "Very soon, we'll be resettling Gush Katif," he shares in an exclusive interview, "We must not forget what the place where we grew up looks like, because we will return."

"The Lettuce That Grew in My Home"

Many agricultural settlements spanned Gush Katif, and Rabbi Elnekaveh pieced them all together like a grand puzzle. "In each settlement, agricultural yeshivas were established. At the center of each settlement, among the greenhouses and crops, one greenhouse became a Torah yeshiva. I would visit a different settlement each day and engage with the students on halachic issues related to agricultural commandments in Israel. It was a Torah powerhouse," he reminisces with longing.

Rabbi Elnekaveh tells us that it was within these greenhouses that the idea of insect-free lettuce, known to us as 'Gush Katif lettuce,' was born. "This lettuce grew in my home. After extensive halachic discussions and comprehensive study of the complex issues, one Saturday night, farmers and agronomists came to my house, and together we successfully developed an insect-free lettuce production line, something we never dreamed could happen."

"For a whole year, I went around to different kosher certification heads, presenting them with the discovery and seeking their halachic approval. I'll never forget when Rabbi Mordechai Eliyahu, of blessed memory, looked at the clean lettuce and jokingly said, 'May it be Hashem's will that the insects move to the other side of Gush Katif, to Deir al-Balah.'"

Is the role of a rabbi in an area like Gush Katif more challenging than in a regular city?

"It's an interesting question," he says. "In general, you could say that a rabbi who serves a city after being a settlement rabbi knows it all. City rabbis only deal with a portion of the Torah systems, such as kashrut, weddings, mikvahs, and synagogues—all challenging areas indeed. But a settlement rabbi also tackles significant challenges related to agriculture commandments tied to the land.

"Additionally, we had to contend with the volatile security situation in Gush Katif. Besides the complex halachic issues, I found myself dealing daily with difficult and painful halachic questions, from cleaning blood of victims of terrorist attacks on Shabbat to evacuating bodies from crime scenes."

Tell us about a significant challenge you faced in your role.

"Every day was its own challenge," he shares. "Days and nights were a marathon of activity. I might start my day with a funeral of murder victims, fully engaged in every phase of purification and burial, and finish it with a bar mitzvah or wedding of Gush Katif children. It's a whirlwind of emotions requiring mental fortitude to keep it together."

To the left: Rabbi Elnekaveh. In the background: Neve Dekalim at its beginnings (Photo: H.A.)

To the left: Rabbi Elnekaveh. In the background: Neve Dekalim at its beginnings (Photo: H.A.)The Rabbi's Law

Often, Rabbi Elnekaveh found himself rushing from scene to scene. These were days when terrorism was at its peak, and he was usually among the first responders at murder scenes. Some victims he administered first aid to, others he buried in the darkest hours. "The peak was after one of the hardest funerals I ever attended. Returning home shattered, I wondered how I could help those widows, widowers, and children affected by terrorism. The next day, I went to Jerusalem, reached the Knesset, and asked for a copy of the Terror Victims' Law. I brought it home, sat with it for days straight, reworking it. My goal was to provide terror victims the same status as fallen soldiers, as at that time, their status was akin to civilians killed in accidents."

"For that entire year, I went to the Knesset weekly, approaching members from all sides, seeking advice, asking questions, writing, and erasing until I felt the law I had drafted was ready to submit. On one such day, a deadly attack happened in Tel Aviv, and then-Speaker of the Knesset, Dov Shilansky, called my house. This was before cellphones became ubiquitous, but my home had a pager from the Binyamin Regional Council. My young son answered the call, and when Shilansky asked for me, my son said, 'Dad's gone to the scene of the attack in Tel Aviv.' They spoke for an hour, and the next afternoon Shilansky called again and told me, 'After speaking to your son, I don't need anything else. Come to me tomorrow, and we'll move this law forward.'"

"The next morning, I traveled to Jerusalem," the rabbi continues. "After offering a prayer at the Western Wall, I went to the Knesset. I needed a Knesset member to submit the law, and I was recommended to speak to the late Hanan Porat. I won't forget when I reached him and presented the law; he began to cry. He said, 'Don't embarrass me by letting me propose a law that won’t pass.' I promised him, 'It will pass.' I had full backing from the Speaker, and indeed, the law passed first, second, and third readings. This law now ensures support for every terror victim nationwide."

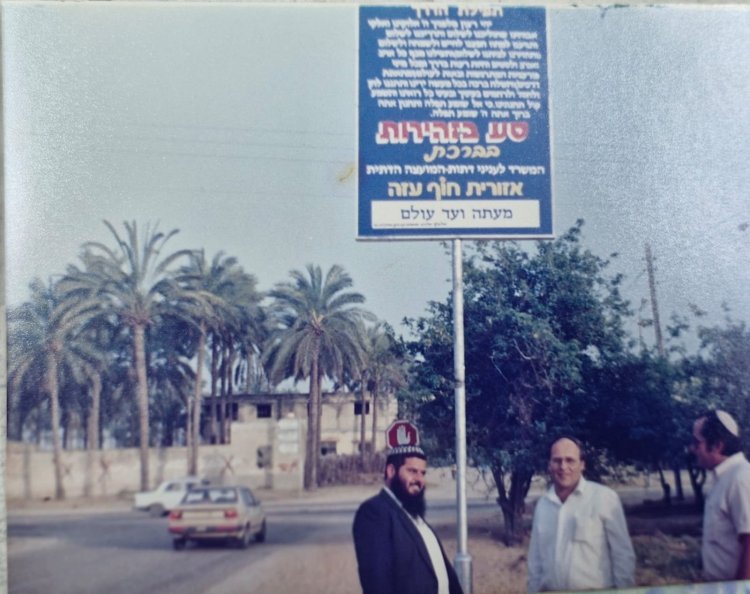

Visit of a rabbi delegation to Gush Katif. Rabbi Elnekaveh in the center (Photo: H.A.)

Visit of a rabbi delegation to Gush Katif. Rabbi Elnekaveh in the center (Photo: H.A.)"What I Told Ariel Sharon"

Nineteen years ago, then-Prime Minister Ariel Sharon executed his Disengagement Plan from Gush Katif. The area's streets and homes were leveled, synagogues and yeshivas closed, and control was handed over to Palestinian authority. Residents found themselves scattered across the country, trying to rebuild their lives.

How did you personally respond to the Disengagement Plan?

"The Expulsion Plan," Rabbi Elnekaveh corrects. "Never call it 'disengagement,' because we never disconnected. I can't forget the endless pain from that time. I looked for comfort and turned to the Book of Tikkunei HaZohar. It said: 'From the time the Temple was destroyed, it was decreed that the homes of the righteous would be uprooted.' I felt like Hashem was speaking to us, saying, 'I have no home, neither will you.'

"You're interviewing me now, exactly 19 years since the expulsion. Go to any journalist who covered it then, and they'll tell you how I tearfully predicted we'd be back in 19 years. I said: 'It took us 19 years to liberate Gush Etzion; it will be the same with Gush Katif.' And behold, a miracle: our soldiers are retaking Gush Katif."

Were you angry with the state?

"Anger isn't the right word," the rabbi clarifies. "We moved heaven and earth, acting both spiritually and practically. On one side, we organized mass prayers; on the other, we initiated public protests. I'll share with you that, at the initial stages, Sharon wanted to first uproot the Gush Katif cemetery. I was suddenly notified of this via a journalist's phone call, informing me that 'they're coming tonight to move the cemetery.' I immediately contacted the Prime Minister's Office, requesting an urgent meeting.

"The meeting took place the next day. I entered his office, opened the Shulchan Aruch before him, and told him: 'Sir, you can read, so please read what happens to those who disturb Jewish graves.' After he read it, I said: 'Don't touch any grave. If you dare touch a single grave in Gush Katif, woe to you from the living and woe to you from the dead.' That's how I put it to him, in those words. An intense debate erupted between us, and nearing the meeting's end, I asked him if he was preparing the IDF for war in Lebanon. He queried my meaning, and I replied: 'I'm neither a prophet nor the son of a prophet, but if you expel us from Gush Katif, a war will erupt in Lebanon.' Indeed, the Second Lebanon War broke out afterward."

"We Will Be Home Soon"

Lastly, Rabbi, do you miss Gush Katif?

"I'm glad you ask," he says with a sigh. "Take all the years since the expulsion, multiply them by the number of days, triple them for the minutes, then again for the seconds. That number equals the longing I have for home."

Do you still call Gush Katif 'home,' even though your current home is elsewhere entirely?

"Gush Katif is my only home. Perhaps now I live in a more permanent house in a more organized settlement, but for me, it's temporary until I return to my permanent home. Soon, we'll all return home to Gush Katif, and I invite you to be the first journalist to cover the return of the Jewish people to the Land of Israel."