From Forensics to Family: One Mother's Unthinkable Journey

Dr. Shira Dishon, a DNA expert at Israel's police forensics department, faced an unimaginable task: identifying bodies from the Shura camp, including her own son's. A poignant interview detailing her struggle between duty and personal grief.

Eitan Dishon. In the circle: his mother Shira.

Eitan Dishon. In the circle: his mother Shira.If you ask Shira Dishon what she's been doing since Simchat Torah, she will tell you that besides the frantic race against time to identify as many of the missing as possible, she has mainly been fighting for sanity and joy. For her, the war has dealt the hardest blow imaginable.

Dishon, a mother of five, with a PhD in Biology and DNA expertise, works in the biological forensics laboratory of the Israeli Police. On a regular day, she's involved in criminal casework, analyzing crime scene evidence to help catch criminals. But since Simchat Torah, her mission turned in a completely new direction – identifying the murdered and creating databases for the missing.

"I remember my husband Dori's phone flashing nonstop. We were about to head to synagogue when he jumped in alarm. He had dozens of missed calls. Realizing something was wrong, he called back. I heard someone say, 'Dori, it's a war, come.'

Eitan with his father

Eitan with his father"In an instant, we were plunged into action: my husband, a reserve Lieutenant Colonel, was called up; my son Eitan, who was in Kiryat Shmona, was rushed into Gaza, fighting in the Givati reconnaissance unit and among the first to enter the Strip; and at work, we began intensively creating databases to identify the dead. As a family, we were involved on all fronts. It was overwhelming, and there was no escape. Both husband, son, and my work – it was exhausting."

How do you maintain sanity during those times, working in forensics with a son in Gaza and a husband in the reserves?

"It divides into two periods: before Eitan fell, when there was a strong sense of mission because often you're on the home front and feel useless, yearning to do more, and here I felt how much I was part of the effort. I knew it was tough work, but it was important, and it gave me strength; and the period afterward, after Eitan fell. Everything changed since then. I haven't returned to the same productivity as before. Emotionally, I can't do it right now. Although I went back to work, the people around me are very supportive, but I do it very, very slowly."

"Our DNA is in every cell of the body, so it can be sampled, for instance, from a cheek swab or blood sample. In the case of the war, we asked families of the missing for toothbrushes, clothes, pacifiers, and bottles if they were children. Behind each item received, there's a name, an ID, a story. At work, we try to emotionally disconnect from the findings we're sampling to stay focused. I'm not comparing what I saw to what those on the ground experienced, a few did visit the Shura camp, but mostly everything arrives here in the lab. It requires lots of sterility, sensitive work, patience, and precision.

"This was also the first time we worked with such a scale, such a huge amount of work. I have to say that often people are pained by how long it took to identify the missing, or that unfortunate errors happened, like realizing later some were buried together, but such things happen when there is such a workload. Yet, if you compare the number of identifications we made in the brief time we had, and with relatively few personnel, for instance compared to the team that handled findings after 9/11 in New York with their resources – we identified a much larger quantity relatively speaking. We worked with the army and the forensic institute in Abu Kabir concurrently, a combined and intensive effort, pooling forces and doing it as best as we could given the circumstances, and really, kudos to all involved for their dedication. There was a need for out-of-the-box thinking, it wasn't easy to reach conclusions. People considered using hospital tests to obtain DNA to reach everyone."

Have you met families of the missing who came to deliver items of their loved ones?

"No, they went to a specific place where police investigators opened a case for each of them. I didn't meet the families personally. But when you suddenly hear another name, and another, that they're missing, and then you sample their evidence and realize they were murdered... it's not simple.

Eitan with his parents

Eitan with his parents"With Eitan, we were fortunate, he fell and there was a body and they could identify him immediately, no need to send DNA. He was identified using other means like fingerprints and dental records because his body was intact. Yet every IDF fallen soldier eventually reaches Shura, so he was there, and I knew he was there, and it was very upsetting. When we were informed that Eitan's body was found in Shura, it was too much, it was overwhelming, realms collided for me."

"The Talmud stained with his blood was a symbolic image of who he was"

Eitan, Shira's eldest, fell fighting in Gaza. On the 7th of Kislev, a rainy, foggy day, the IDF entered Jabalia. Eitan, commanding a Namer, needed to be exposed to prevent vehicle obstruction. A few hours into the battle, a sniper hit him directly in the head. The extraction was quick, yet at the hospital, not much could be done; the medical team had to declare his death.

"Eitan fought in the initial days of combat. We heard from him twice in three weeks since he was drafted, always projecting confidence, never wanting to worry us. He was truly a hero, brimming with self-assurance, faith in Hashem, and great belief. Anytime he needed the Namer fixed, he called from an unidentified number to say hello and returned to battle. A week before he fell, we were granted a touching 48-hour reprieve when Eitan was released for a break. He came home, visited his grandparents, an injured friend in hospital, his Bnei Akiva friends, and we had special time with him.

"Then he was summoned back to base. When we drove him there, there was such a strong sense of unity and bonding between the soldiers, and I felt like I too wanted to go into Gaza," she laughs. "I asked if he wanted not to return, to rest at home, and he said it was his privilege for the Jewish people, his time to give himself fully to the nation. Our last conversation was on Friday. He fell early Monday morning. He hung up, entering Gaza. I always told him he was our hero and that I loved him, and it was the first time he said he loved us too. It worried me, like a farewell. I immediately called Dori asking, 'Why is he saying this?', and he reassured me."

"Eitan was every mother's dream, and I say this totally objectively," she quips. "He was incredibly smart, funny, with a sense of humor, a loving, respectful son, and a true eldest brother: he took responsibility, cared for his siblings, and was truly a friend. He loved Torah deeply, it lit his face and his path, and he was a person of many talents. He connected with Torah from a young age, even in kindergarten, listening to Dori's Bible stories. At the time, I thought all kids were like that, until I learned otherwise. Later, in school, he was immersed in missions of Mishna studies, memorizing many tractates with love. In junior high, he devoted himself to daily Rambam study until he completed it. By eighth grade, he nurtured a new love for the Talmud, studying passionately outside of school.

"In twelfth grade, nearing enlistment, he achieved high scores, eligible for top roles. Like a good son, he followed my directions, attended testing, progressed. At a final stage interview, later told he wasn't accepted, I was surprised. Asked why he thought, he shared they questioned why he'd serve there, and he admitted it was his parents’ wish, not his. He loved Torah, preferring simple service. A significant parental lesson, I realized I pushed him hard, but he needed his own journey. He chose a hesder yeshiva in Kiryat Shmona, which he truly thrived in.

"As a freshman, he was picked among the first to give a major public sermon. Post-sermon, Rabbi Kirshstein, not prone to praise, declared him a future great rabbi and yeshiva head. Eitan never shared, and when asked how it went, he'd modestly say 'it was okay...' At parents' Shabbat, we discovered his commendations. He served as 'meshiv', the go-to student for questions. His clarity and pleasant explanations were profound.

"Come army time, he was assigned to Givati’s recon unit. Unusual for hesder graduates, it was a substantial group. His positive spirit uplifted everyone. After half a year of training, he called unexpectedly, they had their phones confiscated, saying there were rumors they'd be released for a weekend and asked if he could invite them to a barbecue. I agreed, asking how many. '50 guys', he replied, then hung up," she recalls, chuckling. "Unsurprising, he was a homebody, social, loving to bring friends over, share Shabbat meals. Naturally, we prepared to feed 50 hungry soldiers with a day's notice. During the Nine Days, to match the somber time, he held a Masechet conclusion. Reflecting on it, it marked a turning point, uplifting spirits, bolstering resolve, a cohesive spirit boosting everyone."

"One day, he left late for the army. I was working, convinced him to drive by Ammunition Hill, near my workplace, planning to 'show him off'. He entered my work, in uniform with the purple beret, I pointed saying, 'This is mine'. He played along, for everything I said. At my desk, he asked, 'Mom, next year, in yeshiva attire, will you still be as proud?'

"Returning to yeshiva, he made Dori his project, deciding they'd study Daf Yomi together. To his credit, it was impressive. Daily at 7:30 PM, sometimes Dori rushed in minutes prior, anxiously awaiting Eitan's call, and they studied for thirty minutes. Always seeing Eitan with a Talmud, enjoying it thoroughly.

"When we retrieved his belongings a month after he fell, they brought his large base pack and a small one for Gaza essentials. Of all things, Eitan took five books: a Talmud, a book of faith, one of philosophy, a Q&A text, and a reading book. All were stained... the Talmud, stained with his blood, was incredibly potent, a symbolic image of who he was. His commander, not religious, shared that he created a temple inside the Namer."

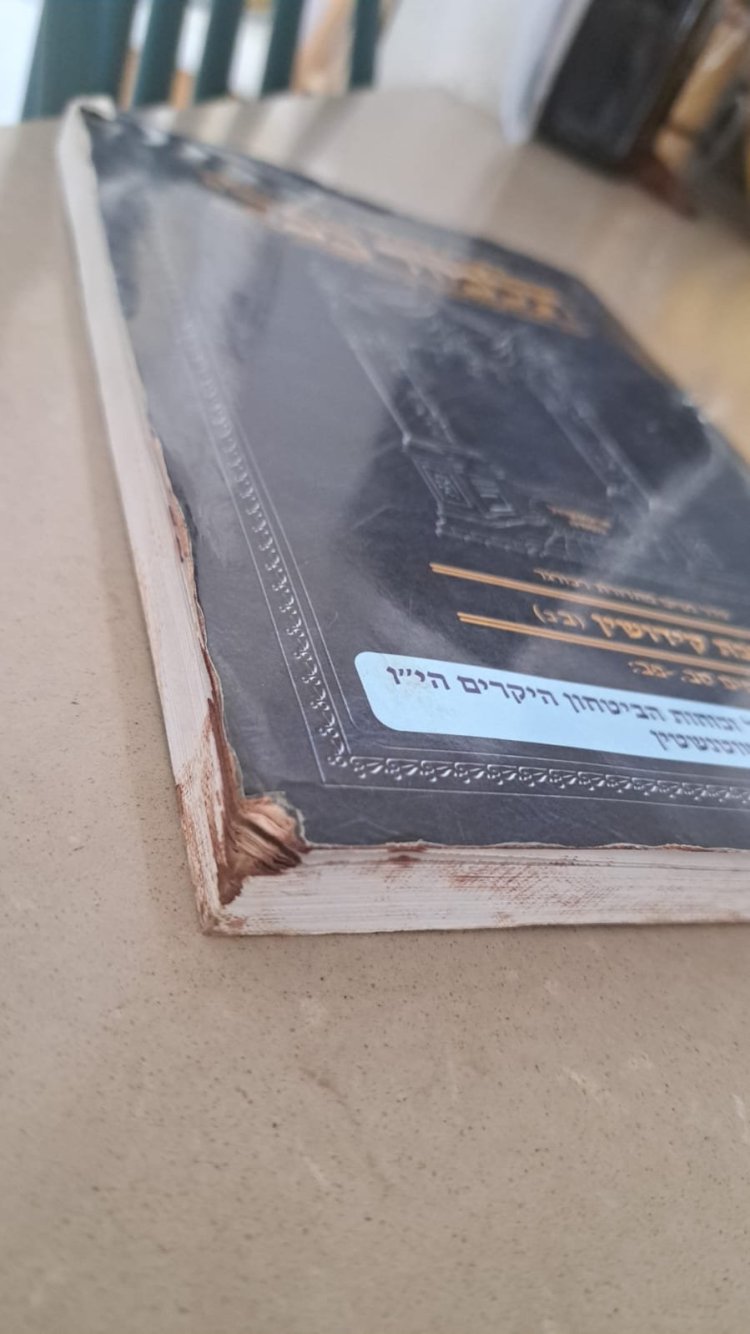

The Talmud stained with Eitan's blood

The Talmud stained with Eitan's bloodShira Dishon was a guest on Moran Kurs' show, "Not Taken for Granted". The full interview will be broadcast soon.